The 2008 Academy Award winning Best Picture, The Hurt Locker, sets combat in the context of addiction, depicting an Explosive Ordnance Disposal expert being unable to keep himself from returning to combat. The film opens with a quote by war correspondent Chris Hedges;

The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug.

Hedges was a reporter in numerous violent conflicts, which he chronicles beautifully in his 2003 War is a Force That Gives us Meaning. Mark Boal, the screenwriter for The Hurt Locker, developed his script through a Playboy article that focused its attention on real life EOD team member Sergeant First Class Jeffrey Sarver. When Sarver sued Bigelow and Boal for making money off his life’s story, Jody Simon, a California lawyer, remarked “Soldiers don’t have privacy.” In effect, martial lives are open for all to see and dissect, that their lives belong not to themselves, but to the public they defend. Or, at the very least, actual lives must never interfere with the fabrication of reality or the inertia of the entertainment industry.

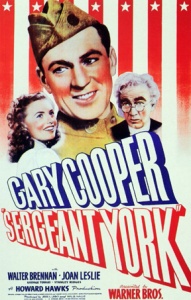

The same troubling assumption was in play when Warner Brothers stretched the truth at the expense of Sergeant Alvin York, a WWI Medal of Honor recipient and conscientious objector depicted by Gary Cooper in the 1941 film “based” on his life. The studio mislead York and stretched poetic license to its breaking point. The finished film only spent a few months in theaters before it was pulled for violation of the Neutrality Acts of the 1930’s. In short, the Justice Department found it to be propaganda used to incite the American public to war in Europe. Nonetheless, it worked (in more ways than one). Adjusted for inflation, it remains one of the highest grossing films of all time. Though it was no longer in theaters by the time Pearl Harbor was bombed, in 1985 the movie was cited as having benefitted recruiting numbers even after the attack (Kennett, pp.156, 160). A win-win, but for who?

The same troubling assumption was in play when Warner Brothers stretched the truth at the expense of Sergeant Alvin York, a WWI Medal of Honor recipient and conscientious objector depicted by Gary Cooper in the 1941 film “based” on his life. The studio mislead York and stretched poetic license to its breaking point. The finished film only spent a few months in theaters before it was pulled for violation of the Neutrality Acts of the 1930’s. In short, the Justice Department found it to be propaganda used to incite the American public to war in Europe. Nonetheless, it worked (in more ways than one). Adjusted for inflation, it remains one of the highest grossing films of all time. Though it was no longer in theaters by the time Pearl Harbor was bombed, in 1985 the movie was cited as having benefitted recruiting numbers even after the attack (Kennett, pp.156, 160). A win-win, but for who?

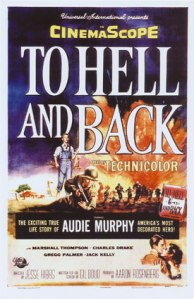

Audie Murphy was one of those young men who went straight from a movie theater to the nearest recruiting depot. He was too young and too short, so he was turned away at first. Eventually, he got his wish when the Army finally accepted him (only after he lied about his age). When he returned from WWII, he wrote about his service as “a brand;” the kind he would have seared onto the hide of a cow on his Texas ranch as a child, or the kind God left on Cain after slaying his brother. His book was made into another very popular war film in 1955, with the movie taking the title from his autobiography, To Hell and Back, in which he starred as himself. When “Murph,” as he was known in Hollywood, drafted a sequel based not on his heroic exploits in war, but on the harrowing return from combat and the transition back to civilian life in the midst of PTSD, no studio was interested. No glory, no green light.

If I am addicted to war, then it follows that the American public is at least as addicted as I am. To be more exact, America is addicted to war fiction, which is often (but not always) to the detriment of warriors themselves. Our culture seems to want the stories our lives make possible, but not the comprehensive context in which those lives find their necessary meaning. As soon as our stories cease to be sensational, we lose any and all critical attention. When the fallout from war gets in the way of the rockets red glare, when the hint of acrid carbon gun smoke sours the flavor of buttered popcorn; who remains the addict, and who needs to think about recovery?

If I am addicted to war, then it follows that the American public is at least as addicted as I am. To be more exact, America is addicted to war fiction, which is often (but not always) to the detriment of warriors themselves. Our culture seems to want the stories our lives make possible, but not the comprehensive context in which those lives find their necessary meaning. As soon as our stories cease to be sensational, we lose any and all critical attention. When the fallout from war gets in the way of the rockets red glare, when the hint of acrid carbon gun smoke sours the flavor of buttered popcorn; who remains the addict, and who needs to think about recovery?

As with any recovery, it comes slow and never without a relapse or two. York made out relatively well, the state of Tennessee granting him land from which he based his work on rural educational reform. But some of his last words on this earth were to his eldest son, whom he asked whether God would forgive him for the 28 Germans who refused to surrender peacefully that fateful day in the Argonne Forrest. Murphy did not do as well, at least not relationally. For the most part, he kept his demons at bay wandering alone at night when the nightmares kept him awake, enacting vigilante justice on the streets of Los Angeles. He was known to be emotionally and physically volatile, slept with a pistol under his pillow, and was even tried for attempted murder in 1970. He knew the devastation war brought to the human soul, and spoke openly about PTSD as the wars in Korea and Vietnam took shape. But what is he remembered for…?

Depicting human lives is reduced to a cost/benefit ratio rather than valued for the power one’s testimony might wield for creating a better, less violent world. We are addicted to entertainment.

We need to give much more attention to the sharp difference between the ways in which war stories have been perceived, depicted and internalized publicly and the ways that it in fact has been experienced, described, and challenged by those who have experienced it personally. Entertainment is king in Hollywood, and it has a dangerous precedent of refusing substantive engagement with the whole trajectory of martial lives. Movies are more expensive to make, of course, and if it isn’t clear to studios that a story will put “asses in seats,” as we said in training blocks during boot camp, then they take the risk. The depiction of human lives is reduced to a cost/benefit ratio instead of being mined for the power a testimony might wield for creating a better, less violent world.

Unfortunately, audiences want to be wowed, not depressed. We are addicted to entertainment for its own sake. Unraveling the complexity of martial virtue is a long game, and (as much as I LOVE Restrepo) deployments last much longer that 90 minutes. Besides, movies are never just entertainment, they are profoundly formative; their production should keep in mind that film affects life (though apparently the inverse doesn’t always prove true).

Understanding war requires we listen to those who have experienced it themselves. Those who have felt war in their hearts and minds tell its story in wildly different ways than those who have not. The old, rather insulting adage, that civilians “don’t know, [because they] weren’t there” proves instructive. We need to stop tokenizing our soldiers and veterans by reducing them to exploitable anecdotes or problems to be fixed. We need those stories of glory and lament together, united by their symbiotic relationship in war. Martial narratives both ancient and contemporary should be the first place we turn for understanding war and its effects, not for filling time on a Saturday night.